Head of Public Policy Tim Dieppe looks at Britain’s ancient Christian roots – including the little-known King Lucius

This year, the nation witnessed the first coronation of a monarch in 70 years: the only coronation in the lifetime of most observers.

It was striking that the coronation was in the context of a Christian act of worship, replete with very explicitly Christian liturgy, vows, and symbols. The whole ceremony obviously had ancient roots, reflecting the long heritage of Christianity in Great Britain. But just how long is that heritage?

It is widely believed that the first Christian King in Britain was King Ethelbert, who converted to Christianity shortly after the missionary Augustine of Canterbury (not to be confused with Augustine of Hippo) arrived from Rome in 597 AD. That gives Christianity a very long and distinguished history in these lands.

However, a strong case can be made that the first Christian king of Britain converted to Christianity some 400 years before King Ethelbert, and that Christianity has an even longer heritage and influence in this country than is generally recognised.

Christianity in Britain before Augustine

Solid evidence for the prevalence of Christianity in Britain prior to the visit of Augustine comes from the fact that the British church sent three bishops to the first Council of Arles in 314 AD.[1] The Church in Roman Britain must have been well established and widely recognised by then to send three bishops to this gathering.

Prior to that, church father Tertullian, writing around 200 AD, said that the “haunts of the Britons” were “inaccessible to the Romans, but subjugated to Christ.”[2] This provides evidence that Christianity was known to be established in Britain by the end of the second century.

The first Christian martyr in Britain was St Alban, who was martyred in the 3rd or 4th century at Verulaminium, which was later renamed St Albans. There were other British Christian martyrs at that time, including Aaron and Julius who are named by church historian Bede.[3]

Around this time Pelagius was born in Britain (c.354 AD) and grew to promote his heretical Pelagian theology. The fact that a prominent heretic arose from Britain is evidence of a vibrant British church at that time.

When Augustine finally did arrive in 597 AD, history relates that the church in what is now Wales refused to recognise his authority, whereupon Augustine ordered a massacre of over 1,000 monks.[4]

All this makes clear that Christianity was very firmly established in Roman Britain prior to the coming of Augustine.

A second century Christian king

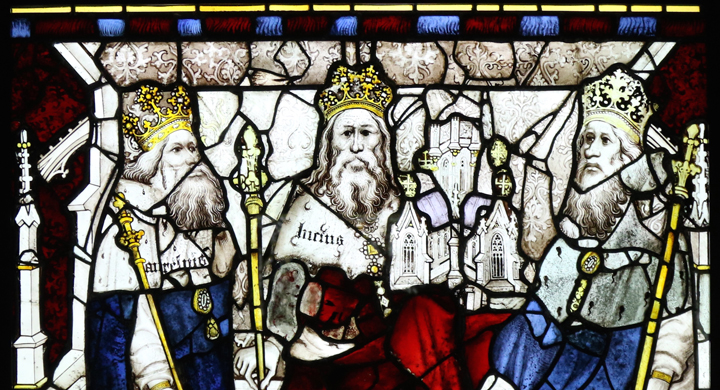

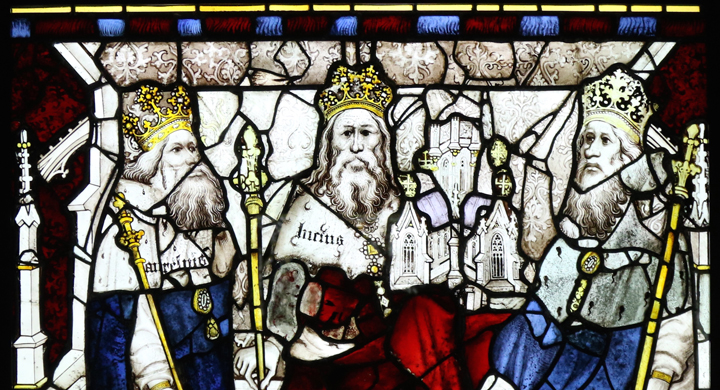

There is a tradition of the first Christian King being King Lucius in the second century AD. This is reflected on the website of St Peter-upon-Cornhill church which says:

“It is widely held that there has been a Christian place of worship on the site of St Peter-upon-Cornhill since 179 AD when Lucius, the first Christian King of Britain, founded it as the first church in London and the chief church of his kingdom.”[5]

The church that now stands on that site was designed by Sir Christopher Wren after the original structure was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

A tabula or brass plate in that church reads as follows:

Bee hit knowne to all men, that in the yeare of our Lord God 179 Lucius the first Christian King of this Land, then called Britaine, founded y first church in London, that is to say, the Church of St Peter upon Cornhill. And he founded there an Archbishops See, and made that Church y Metropolitane and cheife Church of this Kingdome. And so indured y space of 400 yeares and more unto the comming of St Austin the Apostle of England, the which was sent into the land by St Gregory, the Doctor of the Church, in the time of King Ethelbert. And then was the Archbishop’s See and Pall removed from y forsaid Church of St Peter upon Cornhill, unto Dorobernia, that now is called Canterburie, & there it remaineth to this day. And Millet a Monk which came into this land with St Austen was made the first Bishop of London, and his See was made in Pauls Church. And this Lucius King was the first founder of St Peter’s Church upon Cornhill. And he reigned king in this Land after Brute 1245 yeares. And in the yeare of our Lord God 124 Lucius was crowned King. And the years of his reign were 77 yeares. And he was buried (after sone chronicles) at London. And after sone chronicles hee was buried at Glocester, at that place where the order of St Francis standeth now.

What is the truth of this remarkable story?

References to King Lucius

The earliest reference to King Lucius of Britain that we have today is in the Liber Pontificalis or ‘Lives of the Popes’ which dates from around 535 AD. Here we find, under the entry for Eleutherius, Bishop of Rome from c.174 AD to c.190 AD, this statement:

“He received a letter from Lucius, king of Britain, asking him to appoint a way by which Lucius might become a Christian.”[6]

Bede elaborates further. In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, (725 AD) he writes:

“During their reign, and while the holy Eleutherius ruled the Roman Church, Lucius, a British king, sent him a letter, asking to be made Christian by his direction. This pious request was quickly granted, and the Britons received the Faith and held it peacefully in all its purity and fullness until the time of the Emperor Diocletian.”[7]

Welsh historian Nennius (c.796 AD) also makes reference to King Lucius,[8] as do several other notable historians before we get to Geoffrey of Monmouth in the twelfth century (c.1135 AD).

Geoffrey of Monmouth expands on the story, relating that King Lucius wrote to Eleutherius after seeing miracles being wrought by young Christian missionaries. Eleutherius responded by sending two men, Faganus and Duvianus, who preached to Lucius and when he converted, baptised him. Geoffrey says they almost extinguished paganism throughout the island and dedicated several pagan temples to the true God, making them churches. Additionally, ‘Archflamens’ were appointed in London, York, and ‘the City of Legions’.[9]

From where did Geoffrey of Monmouth obtain the details added to the story? Some scholars have accused him of embellishment.[10] But would Geoffrey really have fabricated details like this? I will come back to this later.

Following Geoffrey of Monmouth, the story of King Lucius was accepted and referenced by multiple major historians right through to the end of the nineteenth century. These include: William of Malmesbury (c.AD 1140), Gerald of Wales (AD 1188), Matthew Paris (c. AD 1245), John Foxe (AD 1563), Mathew Parker (AD 1572), Raphael Hollinshead (AD 1586), Archbishop James Ussher (AD 1639), and John Milton (AD 1670).[11]

Lucius written out of history

All this changed in 1904 with a paper by then well-known German theologian Adolf von Harnack who argued that early references to King Lucius of Britain were really a case of mistaken identity. He posited that a scribe confused him with King Abgar VIII of Edessa who did have Lucius as one of his names. On the strength of this paper, all modern editions of Bede contain an endnote describing King Lucius of Britain as a ‘legend’ and saying that references to King Lucius of Britain are actually references to another king.[12]

And so, since Harnack and throughout the twentieth century, King Lucius was written out of history and relegated to a fable.

That was until 2008, when historian David Knight wrote about King Lucius. Knight subjected Harnack’s argument to detailed scrutiny and found that Harnack’s argument does not stack up at all.

For example, King Agbar VIII was never referred to as ‘King Lucius’. Also, King Agbar VIII was already a Christian so why would he ask the Bishop of Rome to help instruct him about Christianity? After demolishing Harnack’s thesis point by point, Knight concludes that Harnack’s “construct proves so untenable that it cannot even be called a hypothesis.”[13] Strong words, but justified in my view. So, what is the historicity of King Lucius?

More evidence of King Lucius

There is extant a document purporting to be a copy of the letter from Bishop Eleutherius replying to King Lucius. This letter was discovered in the archives of London Guildhall in the time of Henry VIII. This copy dates from the thirteenth century, around the time of Magna Carta. Raphael Hollinshead indicated that several copies of this letter were extant in his day (1586), in various states of dilapidation. Archbishop Ussher stated that there were five different manuscripts.[14] None of these are known to be extant today. The full text of the letter we do have is reproduced in Knight’s book. It contains multiple quotes from scripture. Knight claims that: “To this day the monarch of Britain is anointed with sacred oils, as a remembrance of Godly responsibilities so succinctly stated in the Letter of Eleutherius.”[15]

Further evidence of King Lucius comes from a table of archbishops of London which was reproduced by John Stow (1598) which he copied from the now lost Book of British Bishops by Jocelyn of Furness in in the mid twelfth century. This table starts with Thean who is said to be “the first archbishop of London, in the time of Lucius, who built the said church of St. Peter in a place called Cornhill in London, by the aid of Ciran, chief butler to King Lucius.”[16] This adds more credibility to the tradition around St Peter-upon-Cornhill.

As far as the plaque in St Peter-upon-Cornhill goes, there are several references to it that pre-date the great fire of London in 1666, including a reference from the early fourteenth century, as well as references in Hollinshead, Stow, and Ussher.[17] The tradition that this church was founded by King Lucius, therefore, certainly goes back many centuries.

King Lucius is historical

After an exhaustive examination of over 160 sources, many of which I have not touched on here, David Knight concludes that King Lucius is historical and that he reigned for 77 years, making him the longest serving monarch in Britain. Given the length of his reign, Knight argues that “It may be no exaggeration that having ruled so long, his influence and regard stretched throughout all Britain.”[18] This king wrote to the Bishop of Rome, indicating some understanding of church authority at the time, and was subsequently baptised. His influence in establishing churches throughout the land was extensive.

It therefore appears that Britain had one of the first Christian kings in the world! A long-reigning monarch who established multiple churches. This means that Christianity goes back to at least the second century in the UK. But there is more evidence yet to come.

Tysilio’s Chronicle

In 1917, then renowned archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie presented a paper to the British Academy entitled Neglected British History.[19] In this lecture he analysed a forgotten text which he describes as “the fullest account that we have of early British history.” He refers to it as Tysilio’s Chronicle, and states that “the internal evidence shows that it is based on British documents extending back to the first century.”

Tysilio’s Chronicle is a medieval Welsh chronicle held in the Bodleian Library Oxford.[20] This chronicle continues to be neglected to this day since David Knight, after an excellent survey of all the references he can find to King Lucius, appears to have been completely unaware of it.

Some of Tysilio’s Chronicle recounts Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 55 and 54 BC. The account in Tysilio matches Caesar’s account in essential details, but differs in ways that show that it is not dependent on Caesar’s account and instead reflects that history from the point of view of the early Britons themselves. There are other details that no medieval forger could possibly have been aware of. This is why Sir Flinders Petrie concluded that the internal evidence shows that its sources include first century documents.

Tysilio’s chronicle also states that King Lucius sent to Eleutherius to learn about Christianity and then converted to Christianity. He says that Eleutherius sent two teachers and that Lucius was subsequently baptised and went on to close the pagan temples and convert them into churches.[21] Sir Flinders Petrie argued that what Geoffrey of Monmouth described as ‘a very ancient book’ from which he copied, was in fact Tysilio’s Chronicle.

Evidence in support of this includes that Geoffrey of Monmouth states in his Dedication that: “Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford . . . presented me with a certain very ancient book written in the British language.”[22] And at the end of Tysilio’s chronicle a colophon states: “I Walter, archdeacon of Oxford, translated this book from the Welsh into Latin, and in my old age I have again translated it from the Latin into Welsh.”[23] Given the internal evidence that Tysilio is relying on documents going back to the first century, this provides very significant additional evidence for the historicity of King Lucius and his conversion to Christianity.

Britain’s first Christian

Sir Flinders Petrie points out that the Welsh triads claim that a certain man named Bran was imprisoned in Rome for seven years from 51 to 58 AD. Then in AD 58 he “brought the faith of Christ to the Cambrians.” The book of Romans in the New Testament was written around AD 58 which means that there was a well-established church in Rome at that time. Thus, as Petrie writes: “there is nothing in the least improbable in a British hostage in Rome being among converts by AD 58.” From there it is more than 100 years to King Lucius’s conversion – plenty of time for Christianity to become well-known across the land.

Britain’s first Christian King

Britain’s first Christian King was King Lucius, a founder of several churches, including St Peter-upon-Cornhill. He was also Britain’s longest reigning monarch, reigning for 77 years. Christianity most likely arrived in this country in the first century and became well established by the second century. Sadly, King Lucius was relegated to a legendary character by Harnack in 1904. That view does not withstand scrutiny. It is time for King Lucius to be reinstated into the church history of Britain.

Lessons of history

There are two pertinent lessons from this episode of history. One is that we should not be too quick to agree with widely accepted conclusions of modern scholarship. Harnack and others were too quick to dismiss the historicity of King Lucius. Once a respected scholar pronounced it a case of mistaken identity it seems as if that gave everyone else the excuse they needed to relegate King Lucius to myth. Modern scholarship is often too dismissive of ancient history, and we should be sceptical of its tendency to hyper-scepticism.

The second is that Christianity has flourished in these lands for many centuries. In fact, it is likely that the gospel first bore fruit here in the first century. We have a remarkably long and impressive Christian heritage with the influence of Christianity stretching to rulers and kings and many others in authority. We are still reaping the fruit of this heritage to this very day, even though much of it is largely forgotten or dismissed. We can be proud of the influence that Christianity has had in shaping our laws and customs – and indeed our coronations. These traditions all point to the King of Kings and we pray that his kingdom will extend again throughout this land.

Photo by andrewrabbott, used under a Creative Commons licence.

Notes

[1] Schaff, Philip. Ante-Nicene Christianity. A.D. 100-325. Vol. 2, History of the Christian Church. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1884, 182.

[2] Tertullian, Adversus Judaeos, ch. 7, v.4. https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0308.htm

[3] Bede, Ecclesiastical History of England, Book 1, Chap 7

[4] Bede, Ecclesiastical History of England, Book 2, Chap 2.

See also: http://www.annomundi.com/history/bangor.htm

[5] https://stpeteruponcornhill.org.uk/heritage.html

[6] . The Book of the Popes (Liber Pontificalis). Translated by Louise Ropes Loomis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916, 17.

[7] Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. London: Penguin, 1990, 49.

[8] Morris, John, ed. Nennius: British History and the Welsh Annals. Vol. 8. Arthurian Sources. Phillimore & co. Ltd., 1980, 23

[9] Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, Book 4, Chap 19

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Six_Old_English_Chronicles/Geoffrey%27s_British_History/Book_4

[10] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 50-51.

[11] David Knight includes as an appendix a table of 166 references to King Lucius prior to 1904. Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011.

[12] Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. London: Penguin, 1990, 362.

[13] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 30.

[14] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 70.

[15] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 74.

[16] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 93.

[17] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011. 84.

[18] Knight, David J. King Lucius of Britain. History Press, 2011, 133.

[19] Petrie, W. M. Flinders. “Neglected British History.” Proceedings of the British Academy VIII, (1917).

https://archive.org/details/neglectedbritish00petr

[20] Cooper, W. R. After The Flood. Chichester: New Wine Press, 1995, 54. I am indebted to Cooper for alerting me to Petrie’s paper and the significance of it. Cooper also published an annotated translation of this chronicle: Cooper, Bill. The Chronicle of the Early Britons. Creation Science Movement, 2018.

The chronicle is nowadays referred to as Jesus College MS LXI.

[21] Cooper, Bill. The Chronicle of the Early Britons. Creation Science Movement, 2018, 57-58.

[22] Monmouth, Geoffrey of. The History of the Kings of Britain. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. London: Folio Society, 1971, 33.

[23] Cooper, Bill. The Chronicle of the Early Britons. Creation Science Movement, 2018, 118.