Independent public health consultant Kevin Duffy writes on the impact of declining fertility rates, and the need to support young families to choose life

Britain is facing a “baby bust”, we are not having enough children and unless we fix this our country will need significantly higher immigration or suffer economic ruin. This is the stark message being delivered by Miriam Cates MP and her colleagues at the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship – and they are not wrong.

In summary, we need to reverse the decline in our fertility rates and reset our average completed family size back to more than 2.1 from the current 1.9. We need to address the real and perceived barriers that increasingly prevent younger women from starting their families or having their second child. We need our government to enact new, pro-natal policies that will help to overcome the financial difficulties preventing many from becoming new parents. Unless we start having more children, the balance in numbers between those in work and those dependent on them will become unsustainable unless we resort to mass immigration.

When addressing the “baby bust” or a “more children” scenario, we must start talking about the very real impact that elective abortion is having on these numbers. Pro-natal policies need to support and encourage women to choose motherhood rather than further increasing the ease by which they can access an abortion. This might be achieved through changing who pays and mandating better counselling for women considering such a decision, many of whom often feel that there is no other choice.

We should stand with Miriam Cates, calling on our MPs and lobbying government to start addressing this issue, to prioritise and ensure improved financial support for our young families and those yet to become parents.

But let us not wait for the government to act, we need our churches to step up now and to ensure that young families are not just welcome but proactively encouraged and supported. Surely, we should be the ones taking a lead in driving and delivering this “more children” future.

For those who are interested in the details, you can read more below.

Quantifying the Demographic Trilemma – ARC

The Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC) was founded in June 2023 by Canadian psychologist and author Jordan Peterson and British Conservative Peer Baroness Stroud. A key initiative is ARC Research which “exists to advance education, promote research, and develop ideas about the keys to human flourishing and prosperity.” At the beginning of November 2023, ARC published a set of research papers including “Migration, Stagnation, or Procreation: Quantifying the Demographic Trilemma” written by Paul Morland and Philip Pilkington.

The problem being presented by demographer Morland and economist Pilkington is the shifting balance between the numbers of people in work and the increasing numbers of those above the State Pension Age. If we can for a moment excuse the rather derogatory terms ‘old age’ or ‘elderly’, especially given that this is anyone aged just 66 and above, this perceived problem is measured by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) as the Old Age Dependency Ratio (OADR). Demographers and economists worry that an increasing OADR will in turn lead to economic stagnation, as employers find it more difficult to recruit, productivity and innovation slump, and the tax burden becomes unbearable as increasing demands are made by an older population on public services and support. This problem is exacerbated by our falling fertility rates, the number of children born to each woman, that, so far, we have held in balance through increasing immigration.

Morland and Pilkington frame this as a trilemma, in which they suggest that we can only choose two out of three desired outcomes, but we cannot have all three; they list these desired outcomes as low fertility, growth in our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and an absence of rapid immigration. The various combinations of these pairs of desired outcomes are presented as three competing scenarios, “economic stagnation”, “mass migration” and “more children”.

Japan is presented as the archetype of the “economic stagnation” scenario. For decades now it has had low fertility whilst at the same time choosing to restrict immigration, the result being an ageing society and a total population that has been in decline for at least the last ten years. Eschewing immigration has ensured that its population is still more than 98% ethnic Japanese. However, its OADR has been rising steeply and is now above 500 people of pensionable age and over, for every 1,000 people aged sixteen to pension age, more than doubling in just the last twenty years. By all measures, Japan’s economy has been in decline for decades and the government has been spending much more than it receives in taxes, resulting in it having the highest debt-to-GDP of any developed country, more than 250%. Senior politicians and commentators speak of impending social collapse, and there will be, unless Japan’s government can find some way to turn this around, quickly.

In outlining their “mass migration” scenario, Morland and Pilkington point to the UK and show that in the early 1970s our OADR was 250 and now, notwithstanding our low fertility, it is just over 300 (using OECD data); some might have concerns about the potential negative economic impact of this level, but it is far below that of Japan. They suggest that this increase would have been significantly more if our working population had not been added to by legal immigration. They use the ONS’s Immigration Ratio (the percentage of the population made up of first-generation immigrants) to show the changing proportion of our population who were not born in the UK; in 1981 this was 6%, in 2001 just over 8% and in 2021 more than 14%, so an increasing trend.

The authors chose Israel as the country to illustrate their “more children” scenario. Israel has a total fertility rate (TFR), the average number of children born to each woman, of just under three, almost double that of the UK. Using World Bank data, they show that Israel has no need to encourage immigration, it has sufficient young people of its own, and since 1997 its economy has thrived compared with that of the UK or Japan; in the last five years its annual GDP growth has been more than 4% compared to less than 1% here and a below zero, slightly negative, growth in Japan.

Morland and Pilkington undertook this study and their modelling of the trilemma to provide data and talking points for the UK’s policymakers. In the second half of their report, they model each of these three scenarios specifically for the UK, using OADR, the Immigration Ratio and TFR as the key variables.

In their “economic stagnation” model, they assumed that the UK will be able to severely restrict immigration, such that the Immigration Ratio continues to rise from the current 14%, peaks at 16% by 2040 and then falls sharply to about 4% in 2083, sixty years from now. They consider that our already low TFR will continue to fall, much as it has in South Korea, from the current 1.6 to just under 1.0 by 2083. The result is an OADR of more than 525 by 2083, like that in Japan today and no doubt causing the UK similar economic woes.

Their “mass migration” model assumes that the UK can maintain TFR at about the current 1.5 and that an OADR of 350 to 400 is acceptable, even though this is up by about one-third from an ONS stated 280 in 2020. This would result in the Immigration Ratio increasing steeply from the current 14% to at least 37% in 2083. The authors note that they consider these assumptions to be too optimistic, suggesting that TFR is most likely to continue falling due to the increasingly lower birth rates of Generation Z. When they modelled using a TFR of 0.8, equivalent to that in South Korea, they found an Immigration Ratio of 54% by 2083. Based on these more radical assumptions, the authors made a statement that was always destined to be picked out as headline material, setting them up as easy targets for those who want to brand them, and ARC, as racist or at the very least scaremongering.

“In order to keep the economy on a sustainable path, and to reconcile economic growth with low fertility rates, the United Kingdom relies on a high level of immigration. Those who identify as “white British” [sic] are predicted to become a minority group in the United Kingdom around 2070”.

They argue that these much higher rates of immigration would in turn lead to a society stratified by new levels of income inequality and beset with cultural tensions and instability. Thus, painting their “mass migration” scenario as not particularly desirable.

The third model, “more children”, paints a scenario in which the UK reduces its Immigration Ratio from the current 14% to 8% in 2083, whilst also keeping the OADR below 400 during the coming years and reducing this back to below current rates reaching less than 250 by 2083. The essential detail in this model is the authors’ assumption that the UK can raise its TFR immediately to the replacement rate of 2.1 and that this will continue to increase year-on-year to just over 3 by 2083.

The authors conclude that the only path to a thriving society is to have more children, especially when compared with either the cultural breakdown caused by mass immigration or a failing economy due to uncontrolled OADR. They suggest that if we cannot get our fertility rates up, then we and many other countries are headed for troubled waters. With a nod towards the huge challenge that this might present us in contemporary society, they call for government to quickly enact pro-natalist policies and for individuals to step up and assume their responsibility to have more children.

“Baby bust” poll – Miriam Cates

On 06 November, Miriam Cates, Conservative MP for Penistone & Stocksbridge, wrote in The Telegraph about what she called a “baby bust” and highlighted the key issues addressed by Morland and Pilkington in their Trilemma paper. In one of her related tweets, Cates said:

“After a post-war baby boom, Britain now faces a baby bust. Unless we reverse fertility rate decline the economic consequences will be stark. The good news is that the shortage of babies is not due to lack of demand.

Polling shows that 92 per cent of young women want children and that the average number of children desired is 2.4. In other words, if women were able to have the number of children they actually wanted, we wouldn’t have a problem.”

Cates is referring to the findings from a poll conducted by Whitestone Insight on 21-25 September 2023; the poll was commissioned by the New Social Covenant Unit (NSCU) (also referenced to the New Conservatives) to find out more about the barriers preventing women from having the number of children that they would otherwise want. The poll was of 1,502 women aged 18-35 living in the UK, and the responses were weighted to be representative of all UK women aged 18-35. (Miriam Cates and Danny Kruger MP established the NSCU as an initiative focused on promoting public policies that strengthen families and communities.)

In the polling, when women were asked for reasons why they were delaying starting a family, or having fewer children, many of the top reasons given related to the economics of having children; the impact on household finances, wanting to move into a first or larger home, needing to feel financially secure before becoming a mother and worries about losing out on future career progression and salary increases if taking a career break or needing to reduce working hours to fit better with available childcare arrangements. Respondents also expressed worries about their ability to be good mothers and finding a partner who will be supportive when starting a family.

Cates and her colleagues at the NSCU and ARC, want government, the media and policy makers to recognise that the declining fertility rate is a severe problem that needs to be addressed quickly. They lean into the polling results that tell us most women want to have more children but feel unable to do so, on average they want to have 2.4 children, but circumstances overcome that desire, resulting in an overall average fertility rate at just 1.5 currently. When discussing these fertility rates, they express concerns about the possible continued decline as Generation Z starts to replace women of childbearing age from the earlier generations.

Miriam Cates wants new pro-natal policies enacted by government to remove the above mentioned economic and career barriers, whilst also calling for those in public life to start talking-up the positive aspects of motherhood and family.

Analysis of modelling assumptions

We should welcome any public debate about the potential impact of falling birth rates on our economy, culture and society. There is no doubt that this is a significant issue that must be addressed, and quickly. Saying that women need to have more children and that the country needs to control immigration, are not easy matters to raise on a public platform, and those that do, often face accusations of privileged moralising or racism.

The trilemma framework offered by Morland and Pilkington is insightful and will be helpful in shaping and informing further discussion. It is not necessary though to present the three scenarios as competing, with only one being the preferred, the future will probably be a blended version of these. The authors, perhaps deliberately, have chosen to model with assumptions at the extremes, which is bound to provoke debate. We should bear in mind how difficult it is to make future projections for these key indicators and how the underlying assumptions often change.

As an example, the ONS is changing how it measures the OADR to take a fuller account of the changing working pattern of people after they reach the state pension age. A considerable proportion are now choosing to continue working, earning income and paying tax, long after the current age 66. Previous projections modelled by the ONS were assuming that the SPA would rise to 68 in 2035 but the government is now saying that this will not change before 2044. Our immigration systems changed in 2021 to replace the prior free movement when we were members of the EU. The ONS and expert demographers are considering how to improve the accuracy of how we count annual immigration and how this is projected into the future; methods of counting are likely to move away from the International Passenger Survey to one that draws not just on entries and exits at the border but also e.g., changes in tax and benefits records.

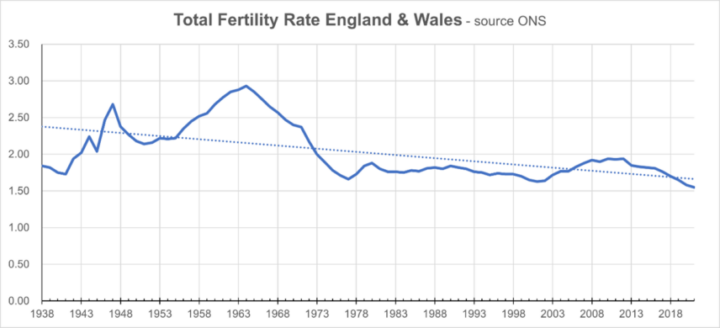

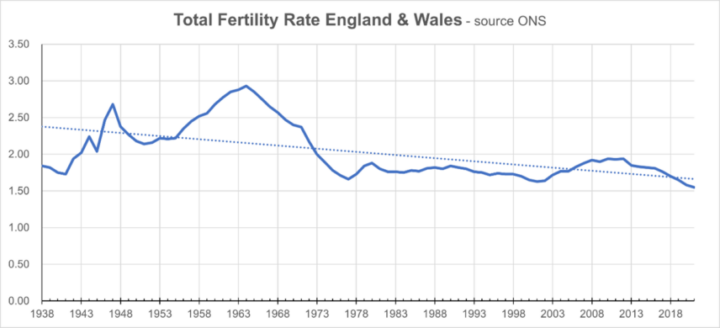

When modelling their “more children” scenario, Morland and Pilkington used an assumed TFR of 2.1 for 2023, rising slowly over the next sixty years to just over 3.0. They made no more than a polite nod towards acknowledging how challenging this might be. In the past eighty years, our TFR has never reached 3, it peaked at 2.85 in 1965, and is currently at a new low of just 1.55; there has been a steady downwards trend over these past eighty years.

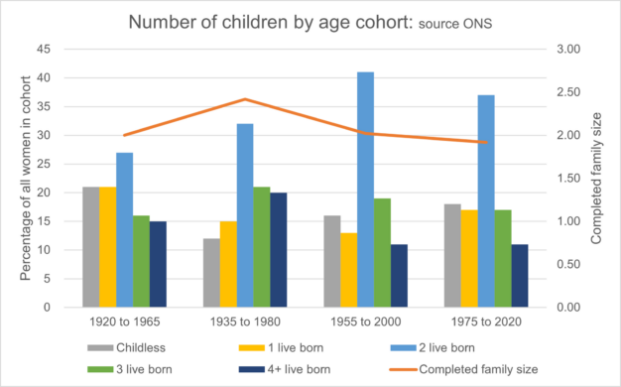

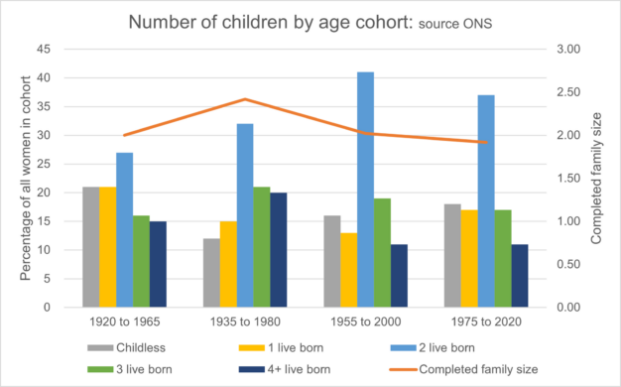

TFR is a snapshot in time, measuring the average fertility across all women aged 15-45 in any particular year, and it can be helpful when considering trends; an alternative measure is the completed family size (CFS), indicating the total number of children that a woman has had in her reproductive lifetime. The ONS provides data for CFS by age cohorts, as shown in this graph.

The most recent cohort is that for women born in 1975 and their completed family size is measured after they reach age 45, in the year 2020. The graph shows an average CFS of 1.92 for this cohort and displays the proportion of women having a particular number of children, e.g., 37% of this cohort have a family of two children and 18% of the women remain childless after age 45. This graph shows a peak in CFS of 2.42 for women born in 1935 and who completed their childbearing by 1980. Comparing these two cohorts we can see that proportionally more women are now likely to remain childless and there are fewer families with 4 or more children.

The polling commissioned by Cates et al., found that younger women, aged 18-35, want on average 2.4 children, reflecting the birth rates and completed family size of earlier generations. This desired CFS stands in stark contrast to the continuing decline in childbearing of women currently in this age group, the younger Millennials and the upcoming Generation Z.

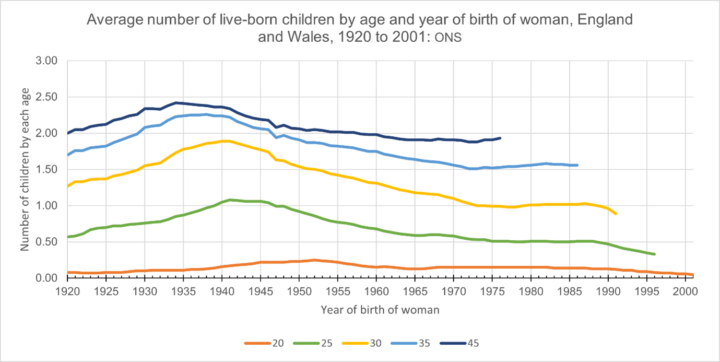

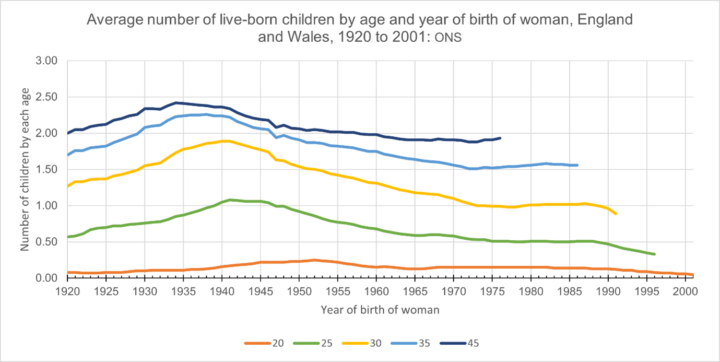

Over the last fifty years, the average completed family size of ~2 children has not really changed for those reaching age 45. However, there are clear downward trends in the number of children women have by the time they reach age 35 and younger; the graph shows a downwards tick in the last couple of years for women aged 30 and a definite downwards trend over the last five years for those aged 25. This shows that women are still having the same number of children, ~2, but they are increasingly more inclined to delay the start of childbearing until age 30+. The issue of concern, as raised by Cates et al., is whether this younger generation will prioritise childbearing in their thirties to catch up and still reach the prior average CFS of 2.1, never mind their stated desired 2.4.

Notwithstanding any instinctive enthusiasm we might have for preferring the “more children” scenario, we must at least agree that the authors have been extremely optimistic when using a starting TFR of 2.1 and assuming that this will continue to rise year-on-year to more than 3.0.

Pro-natal policies

The polling commissioned by Cates and her Conservative colleagues provides some clear indicators of the targets for any new pro-natal policies. These must aim at reducing the financial burden on young families, making it easier for young couples to establish the family home, reducing the cost of childcare (whether paying for nursery placements or loss of earnings when a parent chooses to stay at home) and ensuring adequate protection of employment rights for much longer than the current statutory maternity leave. We should stand with Miriam Cates in lobbying our MPs to support and promote such policies.

It is noteworthy that the ‘A’ word cannot be found in either the Trilemma paper, the polling results, or in any of the pieces written by Cates about these; that seems shortsighted, especially when the core topic is the issue of falling birth rates. We must address the impact of abortion, otherwise the preferred “more children” scenario will remain out of reach.

The completed family size for the most recent cohort, as noted above, is 1.92. It is often reported and widely accepted that one-in-three women will have had at least one abortion in their lifetime. Those abortions have in effect reduced the CFS from at least 2.25 to the current 1.92. Had CFS been 2.25, as Cates notes elsewhere, we would not be facing this crisis and women overall would feel more fulfilled in their desired family size.

Whilst fully supportive of the above listed pro-natal policies, I think we should add the following to the overall mix:

- Remove the NHS funding for all abortions that are for reasons of choice and not medically indicated, those currently certified under Ground C. These could still be available on request in the private sector but paid for directly by the woman herself.

- Mandate in-person counselling for all women electing for an abortion and ensure that the reasons why each woman is considering an abortion are fully explored and that she is made aware of alternative options and any available family support (financial and practical).

Our churches need to step up, we should not wait for the government; we need to be much more encouraging and supportive of young families, now. This would satisfy what Cates is calling for when she encourages those in public life to start talking-up the positive aspects of motherhood and family. Our church families should not be struggling with childcare, and none should feel that their only choice is abortion when worried about not being able to afford their new baby.

It is time to start talking about “more children” and playing our part in making this a near-future reality.